On Luke 24:44-53

I have to admit, I find Ascension Day a little depressing. Look, I get why it’s a festival — Jesus takes his rightful place in heaven, God and man are reconciled — it’s a joyful thing. But I never read these lines from Luke without a tug of melancholy. Let me try to explain why.

In secondary school, my friends were always older kids. Which meant that every year I’d go to the graduation ceremony, where some of my closest pals would graduate before me. So naturally I’d cheer extra loud when they got their diplomas, and I really was happy for them. They’d achieved big things, and I supported them. This was right; it was what was supposed to happen next; the bright new world of university was all before them.

But me, I still had years to go: I was the one getting left behind. And I couldn’t help thinking about what school would be like without them, how while they advanced to bigger and better places I would still be here in our little home town which would now feel grayer, sadder. Actually we’re coming up on the end of Oxford’s academic year now, so maybe some of us here can relate: it’s not easy watching people you love move on. I congratulated them at graduation, but some little part of me was always pleading, ‘don’t go.’

I get this funny sense that maybe the disciples felt something like that at the ascension.

For these last two terms we’ve been studying the creed, the bedrock of our Christian faith. As I see it, at the core of that creed is a story which goes like this: for longer than history records, the human race has had this aching sense that everything good in the world has a personality behind it. We told these tall tales about how love was a beautiful woman or music was a gentle young man — how, as Plato put it, the whole universe had a single soul. The apologist G. K. Chesterton called this ‘the gossip of the gods’: that inarticulate suggestion you can only properly make in a myth or a legend, that when we encounter beauty or virtue or truth we’re meeting someone whose character is expressed in the world.

The Ancient Israelites believed that there was one such someone behind it all, that all excellent things were features of one perfect personality. Knowledge comes from his mouth, says the Book of Proverbs (2:6); pleasures, say the Psalms, are gifts from his hand (16:11). Maybe he called you as you slept, like Samuel. Maybe you heard him speak in the silence, like Elijah. But everyone had some inkling of his presence: when they laughed over a meal with friends or celebrated the birth of a child, they sensed it was because that someone was there: ‘in your presence is fullness of joy’ (Psalm 16:11).

But then — the Christian claim goes — that someone was born. A human man with a human face stood on solid ground and it was him. His sheep heard his voice: the people who were alive back then started to recognise him as ‘the Son of the living God’ whose character their ancestors had tried to describe in their visions and prayers.

So of course he healed the sick and the blind and the paralysed, and we hear all about how unbelievable that was. But what must have been almost as amazing is just the fact that he was there. The one they’d been waiting for, literally in the flesh. He was there spending time with people who never imagined he’d give them the time of day: Zacchaeus the hated tax collector. A woman humiliated in bed with a man who wasn’t her husband. Pariahs no one else wanted to touch, looked in his eyes and talked to him.

The Gospels are full of people just trying to describe what that was like. ‘It’s good for us to be here,’ blurts out Simon Peter standing next to the transfigured Jesus. ‘Lord, if you had been here,’ says Martha of Bethany, ‘my brother wouldn’t have died.’ Jesus himself says that being with him is like having light to see by, and when he leaves it will be like the world goes dark. Goodness, light, life itself: that’s what it meant just to be with him. To spend time with him as a friend.

And after the unspeakable bereavement of watching that friend tortured to death, they had the unheard-of bliss of being reunited with him. They could tell it was him even after he had died, even though that must have seemed impossible. Because when he spoke everything made sense — when he explained the Bible and broke bread and said their names their hearts were filled with gladness. They knew that had to be their guy and no one else, because no one else made you feel that way just by being around. And now, after they just got him back . . . he has to go?!

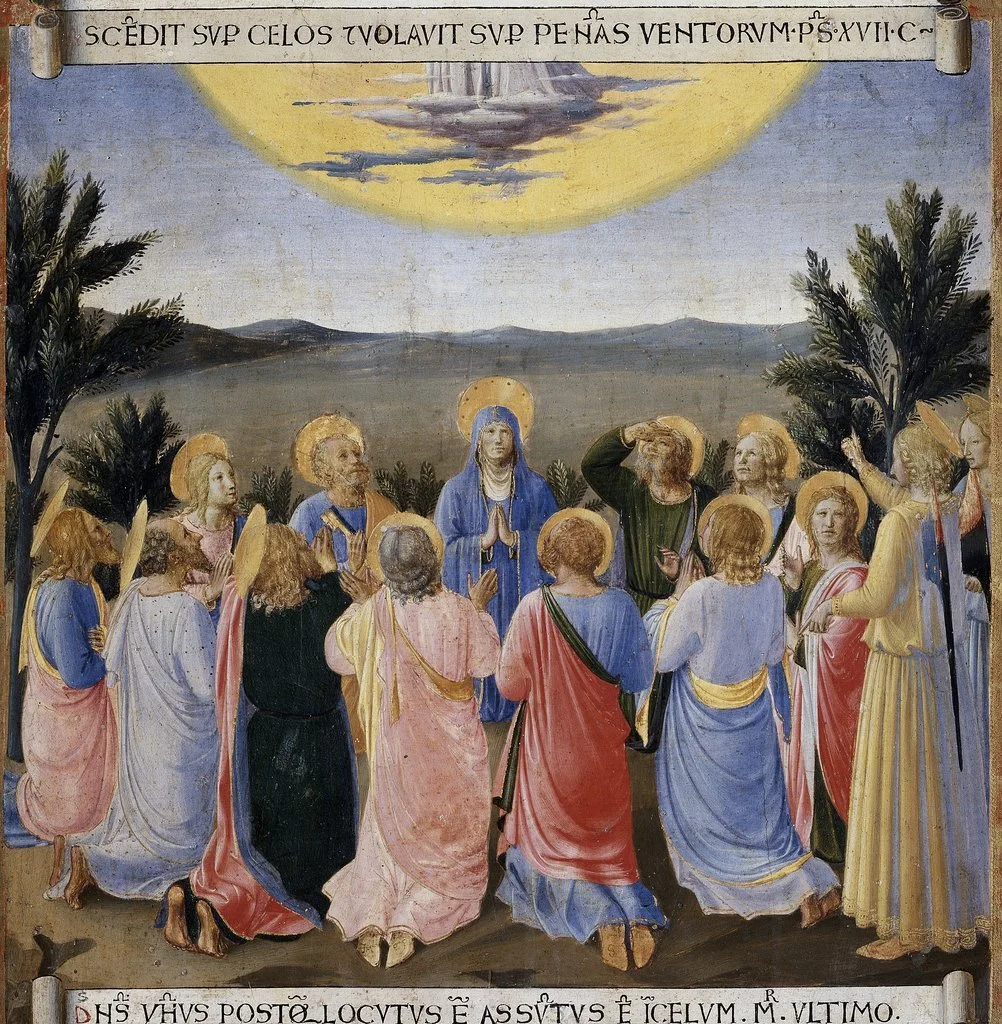

So yeah, this is right, this cloud of glory: it’s what was always supposed to happen since back before Daniel saw one like the Son of Man exalted before the Ancient of Days. That’s where he belongs: he deserves his rightful place in heaven. His work here is done; it’s time for him to move on somewhere better. And his friends rejoice, says the text. But don’t they also feel left behind? He’s headed, as he told them, to a place where they ‘cannot follow.’ In some corner of their hearts, I have to imagine they’re thinking, ‘don’t go.’

I also imagine that everyone reading this has felt that way at some point: like all the color and light went out of the world and left you behind. We’re still here, you and I, on this earth where people who love us get sick and relationships fall apart, where friends die or do hideous things to each other. Three days ago in this world, in Manchester, twenty-two lives were mercilessly extinguished in the murderous name of a false god.

When things like that happen it’s all very nice that Jesus is seated at the right hand of the father, thanks a bunch, but don’t we kind of want him here, now? And why does it feel, in these moments of grief or fear, as if he was never here at all? After Jesus saved the world, wasn’t everything supposed to be better? Has anything changed?

One thing: now we know. That feeling our species had for so long, like there was someone alive in every good thing, someone who spoke to us whenever we found peace, someone we met whenever we experienced love — now we know that feeling was the truth. We Christians believe that that someone stepped out from behind the curtain and said, ‘I am. Here I am.’ Because he did that, now we know.

Which explains something else he said, too. ‘See: I am with you always, until the end of the world.’ How can that be when he’s so clearly gone? Well, maybe there’s a difference between his being among us and his being with us. Maybe even now that he’s not among us on earth, he’s still with us the way he always was: in acts of courage, in words of forgiveness. In the breaking of the bread. I think that’s why, right before he left them, Christ interpreted the scriptures for his disciples, showing them it was him the prophets and the psalmists were describing all along. It’s as if he was saying, to them and to us, ‘look: all that time, I was always with you. Now I’m going, but I’m with you still. And I’m coming back.’

Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again. That’s not a fairytale. It’s not wishful thinking. It’s history, and it’s a promise. It’s the faith we hold that Love himself sent up a flare to let us know we were right, he was speaking to us all along, and he’s speaking to us now. So here in the darkness where he left us, our whole job is to hold up the great light we saw in that flare, to act in his name and believe what he told us. To trust that he’s with us when we fight for justice, when we speak the truth, when we take communion together. That we encounter him, get to know him, even though we’re still waiting for him to come back. That even when we suffer pain and terror like they did in Manchester, when we mourn the fact that he’s not among us yet to make things right, even that yearning for him in our hearts tells us, as it always has, that he has to be out there somewhere. Now we know. He was here. He left footprints on this same ground we walk on. He’s coming back. Now we know that not even death, his or ours, can keep him away. Do not be afraid, but believe: he won’t leave us behind.